1. Hang out with your children.

I was blessed to be a

stay at home mom. But sometimes I found

that with PTA presidency, church and community volunteering, shopping, cooking

and cleaning, and my own projects, the kids didn’t get a lot of my time. One year I was treasurer for the high school

choir where my daughters sang. It

involved time-consuming fund raising.

One daughter asked why I was never home and intimated that I didn’t care

much about them since I was always gone.

It didn’t matter to her that what I was doing was for her benefit, it

only mattered that I wasn’t there for her.

Spending time with

your children means putting everything down.

It doesn’t count if you take your younger child to the park and then sit

on a bench with your tablet. They want

interaction: playing tag, pushing on the swings, admiring their daring on the

bars.

It means showing

affection, respecting their individual personalities, taking a genuine interest

in their lives, talking about things that matter, and affirming their efforts

and achievements.

My sister-in-law had a

great relationship with her children.

When her teens came home from a date, they would look forward to sharing

with her the details, and she would be so excited for them. My children, on the other hand, when asked

about how it went would say, “Fine.”

Period. It could be that rather

than affirming their efforts and being excited for them, I would be judgmental

and preachy. Hmm.

Spending time with them means reading a

book with them when they’re younger, or reading a book they like when they are

older so you can discuss it with them.

It means hiking, kicking a ball, or just playing an old-fashioned board

game. It means that you interact with

your kid person-to-person. Think back to your own childhood. What are your precious memories? Chances are they aren’t what your parents

bought you, but time you spent together, family vacations, one-on-one times

with Mom or Dad.

How can a busy Mom

squeeze this into her schedule when there is so much to do? One way is to include them in what you are doing. Have them help fix dinner, or plant in the

garden. When there are chores to do, do

them together instead of sending them to do the chores alone. Take them with you when you go on errands and

talk together in the car. Have them

assist in any project you are doing. It

is always more difficult and takes longer to have your children “help”, but

what are your priorities? You are

developing a child, both training them in skills, and letting them know they

are valued.

Spending time with

your children is really the foundation of everything else. Ask them open-ended questions about

themselves, about the world and how they see it, and actively listen to their

responses. Accept their views, even if

they are different than your own. Not

only will you learn all sorts of things that make your child unique, you’ll

also be demonstrating to them how to show care and concern for another person.

2. Say it out loud.

If it’s important, say it out loud.

You may feel that they should know that you love them because of all the

things you do for them, but they take that for granted. They need to hear the words, “I love

you.” “Thank you.” “I appreciate it when you…” “That was a good thing you did.”

They need to hear what are the values you think are important. “What can we do to help that person?” “That was kind of you.”

Your child needs to hear that he or she is top priority in your

life. It’s not enough to show them by

giving them things, keeping them safe, or feeding them. Children require acknowledgment through

words. Words are important. One father of a rather rebellious son would say, "I love you more than you will ever know. So I'm going to be checking up on your tonight to make sure you are where you say you are going."

Invite them to sit and share their stories about school, homework,

friends, and so on. Allow your child to

feel comfortable to come and speak with you.

3. Show your child how to solve problems. Don’t stress about the outcome.

My husband taught physics on the University level. He always said the most important thing was

to first understand what the problem is, and then the student could figure out

how to solve it.

Foster creativity. Practice

brainstorming, but if they suggest something ridiculous, don’t say, “Well, that

would never work.” Laugh with them,

maybe follow it through to the ridiculous outcome. By accepting all possible ideas, they can

learn to think outside the box.

Feel free to offer a variety of possible answers to get the ball

rolling. It encourages a child to

consider multiple options and to project possible outcomes.

Be patient while they figure it out.

If their jacket sleeves are inside out and they can’t get their arms in, and they are having a melt-down, instead of just fixing it, give them the time to solve the problem on their

own. If they can’t see a solution, ask

questions: “What are you trying to do?

How can you do that? What would

happen if you stuck your arm in the sleeve, grabbed the end, and pulled it

out? Would that work? Is there someone you can ask to help you?”

When you have a problem, think out loud and let your children listen to

you solve a problem. You can even ask

for their help. It’s remarkable to hear

the possibilities they can come up with.

“The ability to care for others is overwhelmed by anger, shame, envy, or

other negative feelings,” say the researchers.

Helping kids name and process those emotions, then guiding them toward

safe conflict resolution, will go a long way toward keeping them focused on

being a caring individual.

It’s difficult to step back as a parent and watch your child make a

mistake, but it’s important to allow them to fail. As tough as it is, failure provides an

amazing learning opportunity. It tells

them it’s okay to make mistakes. None of

us magically solve every problem the right way. It’s also important to set

clear and reasonable boundaries that they’ll understand are out of love and

concern for their safety.

Nor is there only one solution to a problem. In my husband’s physics lab, the students

were doing experiments with pendulums. A bar clamped to the edge of

the lab table with a cross bar holding the pendulum ball and wire.

All the students were swinging the pendulums

from side to side to take their measurements of arc, time, length, etc. But one set of lab partners were having

problems. They were swinging their

pendulum from front to back and it kept hitting the table. They asked what they should do. All around them other students were swinging

their pendulums back and forth. My

husband told them he thought they could figure it out. When he came back some time later, they had

lowered the cross bar to table height so the pendulum, still swinging front to

back, swung under the table. It wasn’t

the obvious solution, but it worked.

To help them risk failure as they try to learn to solve problems, praise

your child for their efforts, rather than the outcome. “The achievement pressure can have a bunch of

negative results,” says Russ Weissbourd.

“I can see how hard you are

working to figure this out!” “You really

put a lot of effort into this.” “I bet

you are glad you didn’t give up. Your

determination made the difference.” “I knew you could figure it out!”

4. Express gratitude to your child often.

I remember being so

angry with my mother when she wouldn’t thank me for doing something she had

asked me to do, especially if she instead pointed out how I could have done it better. I didn’t say anything (I was a

compliant child), but I’d give her “the look” and think hard thoughts about

her. Never mind that I never thanked her

for what she did for me. That was

different. I resented her apparent lack

of gratitude. So I tried to make gratitude

a routine response for chores done or requests accomplished with my own

children. I found that thank you goes a

long way. Be grateful also for the small acts

they do that have nothing to do with chores or school.

I love it when you hand

a two-year-old something and they say “tank oo”. You know they are just parroting their polite

parents, and probably don’t really feel gratitude, but the habit will teach

them that expressing appreciation is important.

It’s also important to

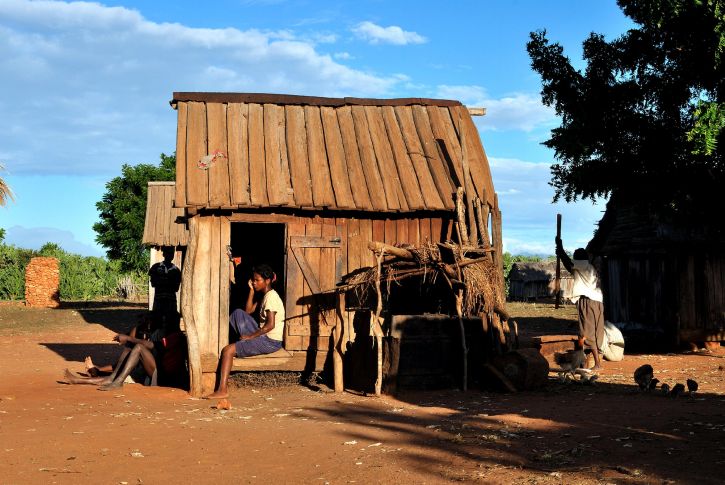

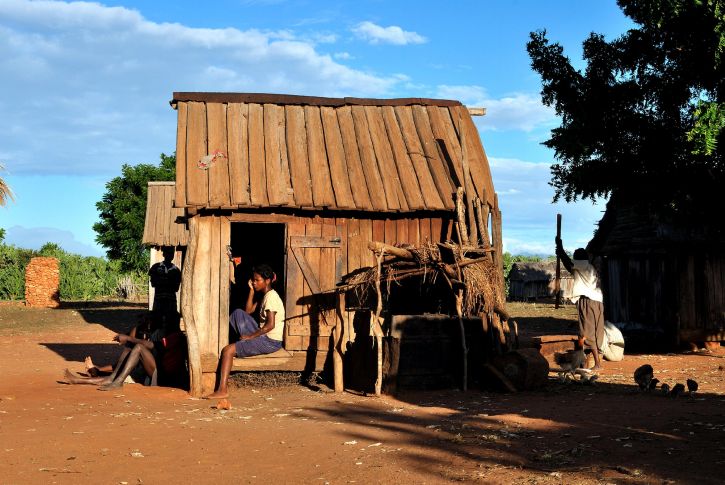

show our children what they have to be grateful for. I remember when my two youngest children had

to share a room with each other and hated it.

I pointed out a cousin in New York that could only afford a two bedroom

apartment but had five children, or the newly immigrated Tongan family we knew

that had two families in one house. I

could have taken them to a homeless shelter, done a charity trip to Mexico,

anything to allow them to witness how fortunate they were to have what they had

at home. This would have taught them not

only gratitude, but empathy and compassion.

5.

Teach your child to see the larger picture.

Ask “How would it affect the team if you quit?” “What will happen later if you don’t eat now?” “How will that child feel if you are mean to

her?”

Helping them see a situation from different viewpoints and from a larger

perspective clarifies their thinking and opens their hearts. Researchers say that “almost all children

empathize with and care about a small circle of family and friends.” We start there, reinforce, and then expand

that circle. Learning chess teaches them to think ahead to the possible outcomes in the future of their actions now.

Teach your child to be a good listener, to put themselves in another’s

shoes, and not judge anyone based on their religion, race, or nationality. Exposing your child to different cultures

helps develop a loving, kind and happy person.

Travel is a wonderful way for your child to experience different cultures

and viewpoints, but if that isn’t feasible, books or other media are another

excellent way. Some families have a

monthly dinner featuring the food from a different country, with the evening

devoted to learning about what’s neat about that country. If your child has an interest in sports, or fashion

design, or armor, you can research together how that differs in different

countries or cultures. Needless to say,

it is important that we model empathy and compassion and care to others in word

and deed.

No comments:

Post a Comment